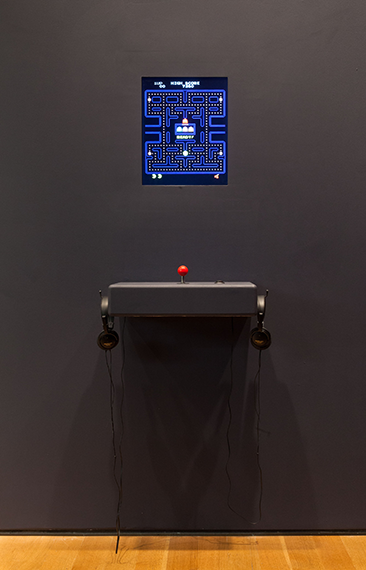

“Pac-Man” (1980) by Tōru Iwatani of NAMCO LIMITED, now NAMCO BANDAI Games Inc. Gift of NAMCO BANDAI Games Inc.

Words // Janelle Zara Artinfo

It’s difficult to distill a singular theme from the wildly diverse exhibits of “Applied Designs,” the latest Museum of Modern Art show organized by senior architecture and design curator Paola Antonelli. Visitors, of course, will flock to play the 14 recently acquired video games. Alongside Pac-Man, Tetris, and Sim-City, however, the arcade-like set-up also contains a roaming mine detonator, various kitchenware, and a wide assortment of chairs (the piece of furniture that the accompanying text describes as the design world’s “right of initiation”) as “boi-oi-oi-oing” sounds resonate throughout the gallery. What exactly is it that they all have in common?

Given the video games and 3-D printed wares (textiles, bowls, and quirky furniture) on view, it would at first seem that Antonelli and assistant curator Kate Carmody had focused on design in the digital realm. Then, the inclusion of objects like The Honeycomb Vase “Made by Bees” (2006), designed by Slovak designer Tomáš Gabzdil Libertíny but constructed by actual bees, dashes that theory. There’s also a sense of whimsy permeating much of the show, from the bee vase to a paper chair that folds flat like an accordion, but that recurring theme is brought up short by the life-saving utilities of Massoud Hassani’s desert-roving detonator “Mine Kafon,” or the sobering theoretical drawings by late architects Douglas Darden and Lebbeus Woods.

What these items do share is their manifestation of Antonelli’s fascination with other worlds. “I’ve always been a science fiction fan, of anything that made me feel like there’s ‘something else’,” she told ARTINFO. The spark for this exhibition in particular was her reading of Edwin Abbott Abbott’s 19th-century parable “Flatland,” a satirical novella in which flat characters live in a two-dimensional world with no comprehension of a third dimension. For Antonelli, each of the included exhibits offers a portal into possibilities which we have no ability to comprehend. “It’s about understanding our limitations. I like to think of what I don’t have as hope of future.”

Even the most static of exhibitions, the image of Ray Tomlinson’s unmoving, two-dimensional “@” symbol (1971), a concept which the museum acquired in 2010, serves as a doorway. The ubiquitous character, painted in a solitary place on one of the gallery walls, links our human identities to our digital ones. Initially it was via email, and now in the infinite universes of Facebook and Instagram, it’s “our passport to enter the digital realm, at the border between flesh and technology,” as the New York Times deftly articulated.

Darden’s drawings of the “Oxygen House Project” (1988), another example, present an alternate dimension beyond a mere building; effectively, the designs serve as the narrative of a fictional disabled character in need of respiratory assistance inspired by William Faulkner’s “As I Lay Dying.” The slow prototyping that created the beeswax vase explores the world of biomimicry in contrast to our fervent development of rapid prototyping technology (the alternate name for 3-D printing); falling in between our technological innovation and utilization of nature is Markus Kayser’s Solar Sinter, a 2011 invention that 3-D prints housewares in the desert using only concentrated sunbeams and sand.

And while the analogy of the video game as a separate, escapist world seems fairly clear, it’s worth noting that the massive multiplayer online roleplaying game (MMO) “Eve Online” was also a favorite pastime of foreign service information management officer Sean Smith, who was killed in the September Benghazi attacks. “He spent his leisure hours building a universe,” said Antonelli. “He saw something in that sort of exercise that was useful for his life.” Following Smith’s death, fellow gamers named landmarks in their shared alternate university after their fallen friend.

“The reason why we don’t understand String Theory is that we have a limitation of sorts,” explained Antonelli, making us like the two-dimensional characters of “Flatland” who reject the concept of the third dimension. As she spoke, the exhibition’s background music moved on from “boi-oi-oi-oings” to the familiar Tetris theme, prompting Antonelli to muse that Jay-Z would want to sample the tune from the PlayStation game vib-ribbon if he heard it. “It kind of sounds like ‘Hard Knock Life’,” she said, further demonstrating that her imagination and resulting ability to link disparate worlds, are endless.